Chapter 15-Transition to Jet Powered Airplanes

Table of Contents

General

Jet Engine Basics

Operating the Jet Engine

Jet Engine Ignition

Continuous Ignition

Fuel Heaters

Setting Power

Thrust to Thrust Lever Relationship

Variation of Thrust with RPM

Slow Acceleration of the Jet Engine

Jet Engine Efficiency

Absence of Propeller Effect

Absence of Propeller Slipstream

Absence of Propeller Drag

Speed Margins

Recovery from Overspeed Conditions

Mach Buffet Boundaries

Low Speed Flight

Stalls

Drag Devices

Thrust Reversers

Pilot Sensations in Jet Flying

Jet Airplane Takeoff and Climb

V-Speeds

Pre-Takeoff Procedures

Takeoff Roll

Rotation and Lift-Off

Initial Climb

Jet Airplane Approach and Landing

Landing Requirements

Landing Speeds

Significant Differences

The Stabilized Approach

Approach Speed

Glidepath Control

The Flare

Touchdown and Rollout

THE STABILIZED APPROACH

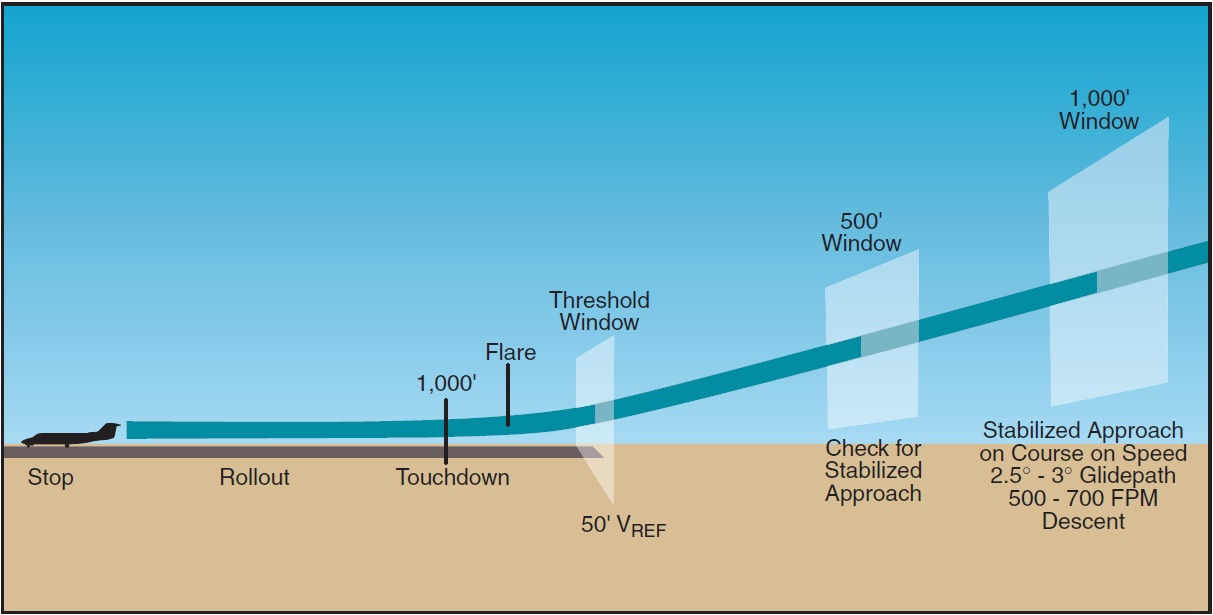

The performance charts and the limitations contained in the FAA-approved Airplane Flight Manual are predicated on momentum values that result from programmed speeds and weights. Runway length limitations assume an exact 50-foot threshold height at an exact speed of 1.3 times VSO. That ôwindowö is critical and is a prime reason for the stabilized approach. Performance figures also assume that once through the target threshold window, the airplane will touch down in a target touchdown zone approximately 1,000 feet down the runway, after which maximum stopping capability will be used.

There are five basic elements to the stabilized approach.

- ò The airplane should be in the landing configuration early in the approach. The landing gear should be down, landing flaps selected, trim set, and fuel balanced. Ensuring that these tasks are completed will help keep the number of variables to a minimum during the final approach.

- ò The airplane should be on profile before descending below 1,000 feet. Configuration, trim, speed, and glidepath should be at or near the optimum parameters early in the approach to avoid distractions and conflicts as the airplane nears the threshold window. An optimum glidepath angle of 2.5 to 3 should be established and maintained.

- ò Indicated airspeed should be within 10 knots of the target airspeed. There are strong relationships between trim, speed, and power in most jet airplanes and it is important to stabilize the speed in order to minimize those other variables.

- ò The optimum descent rate should be 500 to 700 feet per minute. The descent rate should not be allowed to exceed 1,000 feet per minute at any time during the approach.

- ò The engine speed should be at an r.p.m. that allows best response when and if a rapid power increase is needed.

Every approach should be evaluated at 500 feet. In a typical jet airplane, this is approximately 1 minute from touchdown. If the approach is not stabilized at that height, a go-around should be initiated. (See figure 15-24 on the next page.)

Figure 15-24. Stabilized approach.

PED Publication