Chapter 4—Slow Flight, Stalls, and Spins

Table of Contents

Introduction

Slow Flight

Flight at Less than Cruise Airspeeds

Flight at Minimum Controllable Airspeed

Stalls

Recognition of Stalls

Fundamentals of Stall Recovery

Use of Ailerons/Rudder in Stall Recovery

Stall Characteristics

Approaches to Stalls (Imminent Stalls)—Power-On or Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-On

Secondary Stall

Accelerated Stalls

Cross-Control Stall

Elevator Trim Stall

Spins

Spin Procedures

Entry Phase

Incipient Phase

Developed Phase

Recovery Phase

Intentional Spins

Weight and Balance Requirements

FLIGHT AT MINIMUM CONTROLLABLE AIRSPEED

This maneuver demonstrates the flight characteristics and degree of controllability of the airplane at its minimum flying speed. By definition, the term “flight at minimum controllable airspeed” means a speed at which any further increase in angle of attack or load factor, or reduction in power will cause an immediate stall. Instruction in flight at minimum controllable airspeed should be introduced at reduced power settings, with the airspeed sufficiently above the stall to permit maneuvering, but close enough to the stall to sense the characteristics of flight at very low airspeed—which are sloppy controls, ragged response to control inputs, and difficulty maintaining altitude. Maneuvering at minimum controllable airspeed should be performed using both instrument indications and outside visual reference. It is important that pilots form the habit of frequent reference to the flight instruments, especially the airspeed indicator, while flying at very low airspeeds. However, a “feel” for the airplane at very low airspeeds must be developed to avoid inadvertent stalls and to operate the airplane with precision.

To begin the maneuver, the throttle is gradually reduced from cruising position. While the airspeed is decreasing, the position of the nose in relation to the horizon should be noted and should be raised as necessary to maintain altitude.

When the airspeed reaches the maximum allowable for landing gear operation, the landing gear (if equipped with retractable gear) should be extended and all gear down checks performed. As the airspeed reaches the maximum allowable for flap operation, full flaps

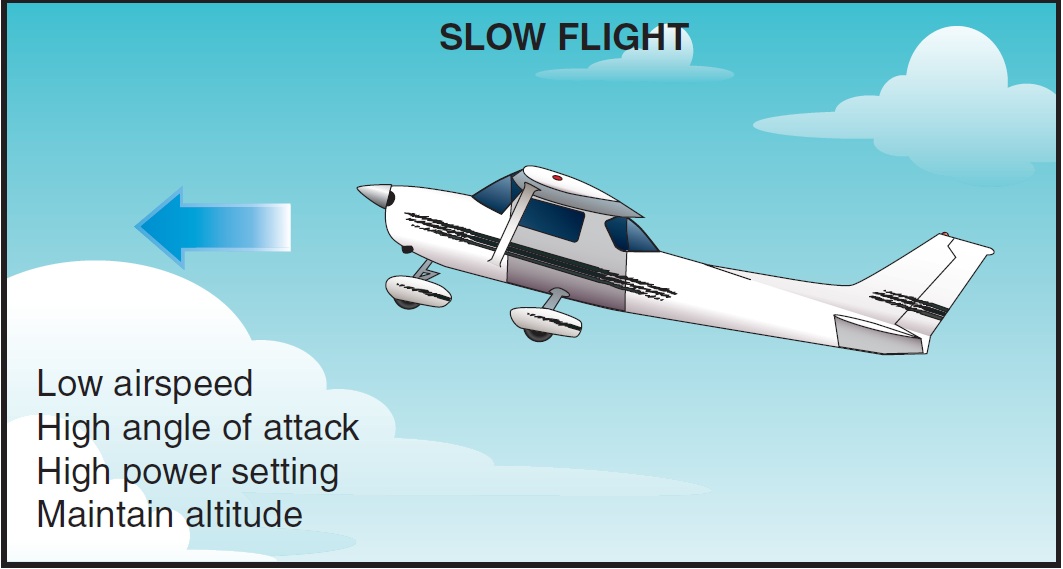

Figure 4-1. Slow flight—Low airspeed, high angle of attack, high power, and constant altitude.

should be lowered and the pitch attitude adjusted to maintain altitude. [Figure 4-1] Additional power will be required as the speed further decreases to maintain the airspeed just above a stall. As the speed decreases further, the pilot should note the feel of the flight controls, especially the elevator. The pilot should also note the sound of the airflow as it falls off in tone level.

As airspeed is reduced, the flight controls become less effective and the normal nosedown tendency is reduced. The elevators become less responsive and coarse control movements become necessary to retain control of the airplane. The slipstream effect produces a strong yaw so the application of rudder is required to maintain coordinated flight. The secondary effect of applied rudder is to induce a roll, so aileron is required to keep the wings level. This can result in flying with crossed controls.

During these changing flight conditions, it is important to retrim the airplane as often as necessary to compensate for changes in control pressures. If the airplane has been trimmed for cruising speed, heavy aft control pressure will be needed on the elevators, making precise control impossible. If too much speed is lost, or too little power is used, further back pressure on the elevator control may result in a loss of altitude or a stall. When the desired pitch attitude and minimum control airspeed have been established, it is important to continually cross-check the attitude indicator, altimeter, and airspeed indicator, as well as outside references to ensure that accurate control is being maintained.

The pilot should understand that when flying more slowly than minimum drag speed (LD/MAX) the airplane will exhibit a characteristic known as “speed instability.” If the airplane is disturbed by even the slightest turbulence, the airspeed will decrease. As airspeed decreases, the total drag also increases resulting in a further loss in airspeed. The total drag continues to rise and the speed continues to fall. Unless more power is applied and/or the nose is lowered, the speed will continue to decay right down to the stall. This is an extremely important factor in the performance of slow flight. The pilot must understand that, at speed less than minimum drag speed, the airspeed is unstable and will continue to decay if allowed to do so.

When the attitude, airspeed, and power have been stabilized in straight flight, turns should be practiced to determine the airplane’s controllability characteristics at this minimum speed. During the turns, power and pitch attitude may need to be increased to maintain the airspeed and altitude. The objective is to acquaint the pilot with the lack of maneuverability at minimum speeds, the danger of incipient stalls, and the tendency of the airplane to stall as the bank is increased. A stall may also occur as a result of abrupt or rough control movements when flying at this critical airspeed.

Abruptly raising the flaps while at minimum controllable airspeed will result in lift suddenly being lost, causing the airplane to lose altitude or perhaps stall.

Once flight at minimum controllable airspeed is set up properly for level flight, a descent or climb at minimum controllable airspeed can be established by adjusting the power as necessary to establish the desired rate of descent or climb. The beginning pilot should note the increased yawing tendency at minimum control airspeed at high power settings with flaps fully extended. In some airplanes, an attempt to climb at such a slow airspeed may result in a loss of altitude, even with maximum power applied.

Common errors in the performance of slow flight are:

- Failure to adequately clear the area.

- Inadequate back-elevator pressure as power is reduced, resulting in altitude loss.

- Excessive back-elevator pressure as power is reduced, resulting in a climb, followed by a rapid reduction in airspeed and “mushing.”

- Inadequate compensation for adverse yaw during turns.

- Fixation on the airspeed indicator.

- Failure to anticipate changes in lift as flaps are extended or retracted.

- Inadequate power management.

- Inability to adequately divide attention between airplane control and orientation.

PED Publication