Chapter 16 Emergency Procedures

Table of Contents

Emergency Situations

Emergency Landings

Types of Emergency Landings

Psychological Hazards

Basic Safety Concepts

General

Attitude and Sink Rate Control

Terrain Selection

Airplane Configuration

Approach

Terrain Types

Confined Areas

Trees (Forest)

Water (Ditching) and Snow

Engine Failure After Takeoff (Single-Engine)

Emergency Descents

In-Flight Fire

Engine Fire

Electrical Fires

Cabin Fire

Flight Control Malfunction / Failure

Total Flap Failure

Asymmetric (Split) Flap

Loss of Elevator Control

Landing Gear Malfunction

Systems Malfunctions

Electrical System

Pitot-Static System

Abnormal Engine Instrument Indications

Door Opening In Flight

Inadvertent VFR Flight Into IMC

General

Recognition

Maintaining Airplane Control

Attitude Control

Turns

Climbs

Descents

Combined Maneuvers

Transition to Visual Flight

TERRAIN TYPES

Since an emergency landing on suitable terrain resembles a situation in which the pilot should be familiar through training, only the more unusual situation will be discussed.

CONFINED AREAS

The natural preference to set the airplane down on the ground should not lead to the selection of an open spot between trees or obstacles where the ground cannot be reached without making a steep descent.

Once the intended touchdown point is reached, and the remaining open and unobstructed space is very limited, it may be better to force the airplane down on the ground than to delay touchdown until it stalls (settles). An airplane decelerates faster after it is on the ground than while airborne. Thought may also be given to the desirability of ground-looping or retracting the landing gear in certain conditions.

A river or creek can be an inviting alternative in otherwise rugged terrain. The pilot should ensure that the water or creek bed can be reached without snagging the wings. The same concept applies to road landings with one additional reason for caution; manmade obstacles on either side of a road may not be visible until the final portion of the approach.

16-4When planning the approach across a road, it should be remembered that most highways, and even rural dirt roads, are paralleled by power or telephone lines. Only a sharp lookout for the supporting structures, or poles, may provide timely warning.

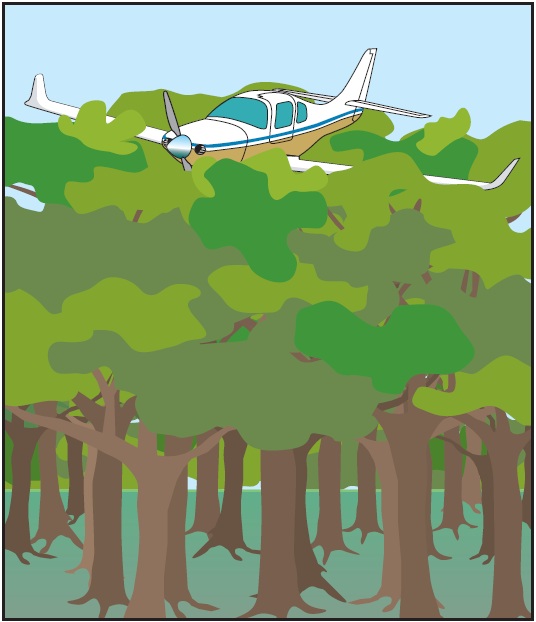

TREES (FOREST) Although a tree landing is not an attractive prospect, the following general guidelines will help to make the experience survivable.- • Use the normal landing configuration (full flaps, gear down).

- • Keep the groundspeed low by heading into the wind.

- • Make contact at minimum indicated airspeed, but not below stall speed, and “hang” the airplane in the tree branches in a nose-high landing attitude. Involving the underside of the fuselage and both wings in the initial tree contact provides a more even and positive cushioning effect, while preventing penetration of the windshield. [Figure 16-4]

- • Avoid direct contact of the fuselage with heavy tree trunks.

- • Low, closely spaced trees with wide, dense crowns (branches) close to the ground are much better than tall trees with thin tops; the latter allow too much free fall height. (A free fall from 75 feet results in an impact speed of about 40 knots, or about 4,000 f.p.m.)

- • Ideally, initial tree contact should be symmetrical; that is, both wings should meet equal resistance in the tree branches. This distribution of the load helps to maintain proper airplane attitude. It may also preclude the loss of one wing, which invariably leads to a more rapid and less predictable descent to the ground.

- • If heavy tree trunk contact is unavoidable once the airplane is on the ground, it is best to involve both wings simultaneously by directing the airplane between two properly spaced trees. Do not attempt this maneuver, however, while still airborne.

Figure 16-4. Tree landing.

WATER (DITCHING) AND SNOW

A well-executed water landing normally involves less deceleration violence than a poor tree landing or a touchdown on extremely rough terrain. Also an airplane that is ditched at minimum speed and in a normal landing attitude will not immediately sink upon touchdown. Intact wings and fuel tanks (especially when empty) provide floatation for at least several minutes even if the cockpit may be just below the water line in a high-wing airplane.

Ch 16.qxd 5/7/04 10:30 AM Page 16-5Loss of depth perception may occur when landing on a wide expanse of smooth water, with the risk of flying into the water or stalling in from excessive altitude. To avoid this hazard, the airplane should be “dragged in” when possible. Use no more than intermediate flaps on low-wing airplanes. The water resistance of fully extended flaps may result in asymmetrical flap failure and slowing of the airplane. Keep a retractable gear up unless the AFM/POH advises otherwise.

A landing in snow should be executed like a ditching, in the same configuration and with the same regard for loss of depth perception (white out) in reduced visibility and on wide open terrain.

PED Publication