Chapter 13 Transition to Tailwheel Airplanes

Table of Contents

Tailwheel Airplanes

Landing Gear

Taxiing

Normal Takeoff Roll

Takeoff

Crosswind Takeoff

Short-Field Takeoff

Soft-Field Takeoff

Touchdown

After-Landing Roll

Crosswind Landing

Crosswind After-Landing Roll

Wheel Landing

Short-Field Landing

Soft-Field Landing

Ground Loop

AFTER-LANDING ROLL

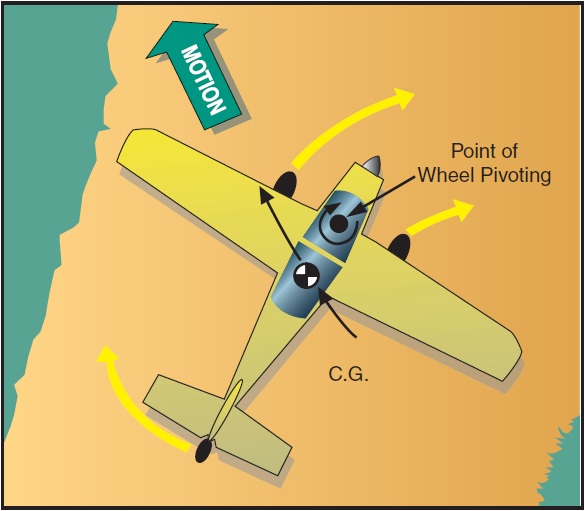

The landing process must never be considered complete until the airplane decelerates to the normal taxi speed during the landing roll or has been brought to a complete stop when clear of the landing area. The pilot must be alert for directional control difficulties immediately upon and after touchdown due to the ground friction on the wheels. The friction creates a pivot point on which a moment arm can act. This is because the CG is behind the main wheels. [Figure 13-2]

Figure 13-2. Effect of CG on directional control.

Any difference between the direction the airplane is traveling and the direction it is headed will produce a moment about the pivot point of the wheels, and the airplane will tend to swerve. Loss of directional control may lead to an aggravated, uncontrolled, tight turn on the ground, or a ground loop. The combination of inertia acting on the CG and ground friction of the main wheels resisting it during the ground loop may cause the airplane to tip or lean enough for the outside wingtip to contact the ground, and may even impose a sideward force that could collapse the landing gear. The airplane can ground loop late in the after-landing roll because rudder effectiveness decreases with the decreasing flow of air along the rudder surface as the airplane slows. As the airplane speed decreases and the tailwheel has been lowered to the ground, the steerable tailwheel provides more positive directional control.

13-4

Ch 13.qxd 5/7/04 10:04 AM Page 13-5

To use the brakes, the pilot should slide the toes or feet up from the rudder pedals to the brake pedals (or apply heel pressure in airplanes equipped with heel brakes). If rudder pressure is being held at the time braking action is needed, that pressure should not be released as the feet or toes are being slid up to the brake pedals, because control may be lost before brakes can be applied. During the ground roll, the airplane’s direction of movement may be changed by carefully applying pressure on one brake or uneven pressures on each brake in the desired direction. Caution must be exercised, when applying brakes to avoid overcontrolling.

If a wing starts to rise, aileron control should be applied toward that wing to lower it. The amount required will depend on speed because as the forward speed of the airplane decreases, the ailerons will become less effective.

The elevator control should be held back as far as possible and as firmly as possible, until the airplane stops. This provides more positive control with tailwheel steering, tends to shorten the after-landing roll, and prevents bouncing and skipping.

If available runway permits, the speed of the airplane should be allowed to dissipate in a normal manner by the friction and drag of the wheels on the ground. Brakes may be used if needed to help slow the airplane. After the airplane has been slowed sufficiently and has been turned onto a taxiway or clear of the landing area, it should be brought to a complete stop. Only after this is done should the pilot retract the flaps and perform other checklist items.

PED Publication